- Home

- Ted W. Baxter

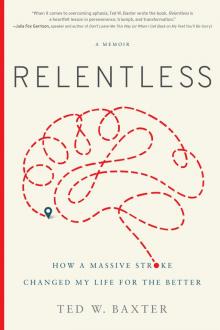

Relentless

Relentless Read online

PRAISE FOR RELENTLESS

“When it comes to overcoming aphasia, Ted W. Baxter wrote the book. Relentless is a heartfelt lesson in perseverance, triumph, and transformation.”

—JULIA FOX GARRISON, speaker and author of Don’t Leave Me This Way (or When I Get Back on My Feet You’ll Be Sorry)

“I know what it feels like to lose everything because of a stroke, and I recognize Ted’s determination to make as complete a recovery as possible. Relentless is an inspiring story that I hope encourages others to approach their own recovery with the same resilience.”

—KEVIN SORBO, actor, director, and author

“In Relentless, author Ted Baxter survives an extensive stroke and devotes himself to making the fullest recovery possible. This process is truly remarkable. Mr. Baxter’s focus, motivation, and successful reestablishment of neurological function are a testament to the human spirit. By accessing the best available clinical expertise and rehabilitation programs, the author is able to begin a new life in which he dedicates himself to helping others. Relentless conveys two important messages. First, the human brain is extraordinarily plastic—it has the ability to use inputs (rehabilitative, among others) to make new circuits that make new functions possible. Second, there is a clear need for us to be able to identify individuals who are at the greatest risk for a stroke after a mini-stroke (transient ischemic attack) or for secondary stroke. This latter unmet need is a problem that modern science and medicine must address in order to reduce the prevalence of stroke and its lifelong impact.”

—HOWARD J FEDEROFF, MD, PhD, professor of neurology, and former dean, University of California, Irvine, School of Medicine

“Ted’s inspirational story about his recovery from a near fatal stroke is extraordinary. His force of will through a combination of courage, determination, and unrelenting resilience in the fight back from those earliest days to where he is now is profoundly inspirational.”

—GERALD BEESON, chief operating officer, Citadel

“I have known Ted since almost the beginning of his remarkable aphasia journey. His persistence and steadfastness in pursuit of regaining his life is inspirational, and his story needs to be heard. Throughout his recovery, Ted has maintained his grace, his good humor, his concern for others, and his broad interests. I am honored to have learned from him. His book will serve as a model for others who have had their lives touched by this devastating problem.”

—AUDREY L. HOLLAND, PhD, regents professor emerita, University of Arizona

“Nearly 800,000 Americans suffer a stroke each year, and those lucky enough to survive are often left with some level of disability. It’s inspiring to read Relentless and get a glimpse of Ted’s strength and determination during such an arduous time.”

—ERIC HASELTINE, PhD, neuroscientist, and author of Brain Safari

“In Relentless, Ted Baxter shares his experience of recovering from a stroke and the challenges and frustrations of aphasia. His determination to not let his stroke disable him and the entire process of rehabilitation and recovery can serve as an inspiration for stroke survivors and their families and loved ones.”

—LOUIS R. CAPLAN, MD, professor of neurology, Harvard University

“Relentless is an astonishing memoir of a man who had everything needed to succeed in life and suddenly lost it because of a stroke. Now reenergized, relearning, and recovering, Ted shares wisdom and the pieces of his completely different, new, and improved life in this inspiring book.”

—JUAN PUJADAS, retired global advisory leader and vice chairman, PwC International LLC

“Of all the patients with stroke I’ve cared for, Ted is easily the most remarkable. I have never seen anyone with a stroke such as his make the astounding recovery he did. And I might also add that the title for his book is apropos!”

—JESSE TABER, MD, NorthShore University HealthSystems

“Ted’s passion and determination led to his miracle recovery from a massive stroke. A truly inspiring book for everyone!”

—WENGUI YU, MD, PhD, professor of clinical neurology, and director, Comprehensive Stroke & Cerebrovascular Center, University of California, Irvine

“This book is a most personal and poignant account of suffering a stroke and experiencing the painful challenges of its aftermath. This could happen to any of us, and Relentless gives us deep insight into what that experience is like along with the challenges of recovery. Many of us may not be so determined (or lucky). Well done, Ted Baxter, for sharing your story with such wonderful and heartening insights.”

—MARK AUSTEN, chairman of Alpha Bank, ex managing partner of financial services consulting at PWC, and director of PWC Global Board

“As an occupational therapist who has specialized in rehabilitating stroke survivors for thirty years, I must say I found Ted Baxter’s memoir to be inspirational and at times miraculous. This memoir is required reading for healthcare professionals to obtain critical insights from a patient’s perspective. Stroke survivors and their loved ones are sure to be influenced by Ted’s resilience, courage, and motivation. This memoir is a gift to the stroke survivor community.”

—GLEN GILLEN, EdD, OTR, FAOTA, Columbia University, New York City, New York

“This book is an inspirational story of the significance of daily perseverance and taking responsibility for your own future by setting incremental and achievable goals. Ted’s writing is not only motivational but a useful guide to the world of recovery for stroke survivors and their caregivers.”

—JONATHAN BURKE, president, Laguna College of Art and Design

“Relentless is a wonderful story that turns tragedy into triumph. I am very proud of Ted’s accomplishments. He is an inspiration for all to never give up.”

—DEAN REINMUTH, world-renowned golf coach, spokesperson, and television personality

The information provided in this book is based on my recollection of events and conversations to the best of my ability. Others may have different memories, and conversations may have been reconstructed. It is designed to provide helpful information on the subjects discussed. This book is not meant to be used to diagnose or treat any medical condition. For diagnosis or treatment of any medical problem, consult your own physician. References are provided for informational purposes only and do not constitute endorsement of any websites or other sources.

Published by Greenleaf Book Group Press

Austin, Texas

www.gbgpress.com

Copyright ©2018 Ted W. Baxter

All rights reserved.

Thank you for purchasing an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright law. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission from the copyright holder.

Distributed by Greenleaf Book Group

For ordering information or special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Greenleaf Book Group at PO Box 91869, Austin, TX 78709, 512.891.6100.

Design and composition by Greenleaf Book Group

Cover design by Greenleaf Book Group

Aphasia Guide reproduced by permission of Archeworks.

©Artisticco. Used under license from Shutterstock.com

©RomanYa. Used under license from Shutterstock.com

Publisher’s Cataloging-in-Publication data is available.

Print ISBN: 978-1-62634-520-1

eBook ISBN: 978-1-62634-521-8

Part of the Tree Neutral® program, which offsets the number of trees consumed in the production and printing of this book by taking proactive steps, such as planting trees in direct proportion to the number of trees used: www.treeneutral.com

Printed in the United States of America

on acid-free paper

18 19 20 21 22 23 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

First Edition

CONTENTS

Foreword

Part 1: Tragedy

Chapter 1: Four Days, Four Flights

Chapter 2: Hours Tick Away

Chapter 3: A Massive Stroke!

Chapter 4: Game Changer

Chapter 5: Can’t Is a Four-Letter Word

Chapter 6: I’m Okay, Except I’m Not

Chapter 7: Not Fast Enough

Part 2: Early Life

Chapter 8: Relentless Since Birth

Chapter 9: Pedal to the Metal

Chapter 10: Moving, Moving, Moving: Out, Up, Everywhere

Chapter 11: I Wanted More

Part 3: Building a New Path

Chapter 12: Turning Point

Chapter 13: Setback . . . a Seizure?!

Chapter 14: I Decided to Win

Chapter 15: No More Limits

Chapter 16: Taking Charge Again

Chapter 17: Expanding Creativity

Chapter 18: Sports as My Recovery

Chapter 19: Life Changes

Chapter 20: Fresh House, Fresh Start, and Socialization

Part 4: Giving Back

Chapter 21: Therapy and Volunteering in Southern California

Chapter 22: Hello, Positive

Chapter 23: In Retrospect

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

Appendix A: How I Did It: The Techniques and Activities That Led to My Post-Stroke Recovery

Appendix B: Sample of Therapy Exercises

Questions for Discussion

Author Q&A

About the Author

Foreword

This book is Ted’s story. Although Ted had a stroke at a young age, and this book describes his life before, during, and after this life-changing event, the story he tells is not one of sadness, of tragedy, or of negativity. Instead, it is a happy and hopeful narrative of determination, of relentlessness, of succeeding at one of the most difficult challenges of his life.

Ted compares this challenge to others in his life, from scholastic achievement and funding his own college education to building a new financial services consulting practice in Japan. Through his efforts, he finds that success has many different measuring sticks, and by the end of the book, readers will not only understand Ted’s success but also gain some insight into how to harness Ted’s magic potion for their own personal quests.

Ted’s story is a pleasure and an inspiration to read. As a speechlanguage pathologist and a neurologist, we are quite familiar with stroke and the challenges of recovery. Yet Ted brings us with him on an intimate journey following a massive stroke that devastated a quarter of his brain. Left unable to walk or talk, every day was a struggle, not only for Ted but also for his wife and siblings. This book would have seemed impossible then. It stands now not only as his memoir but as testimony to the power of sheer determination.

Ted had a stroke at forty-one. Strokes (also known as “cerebrovascular accidents” or “cerebral infarctions”) can come in many different forms and can be extremely severe or quite mild. Some strokes are caused by blood clots that block major arteries in the brain, others are caused by bleeding in the brain from the breakage of large vessels with abnormal walls (i.e., aneurysms), and still others by the blockage or breakage of very small vessels (e.g., arterioles). The United States Public Health Service and independent stroke support organizations, such as the American Stroke Association, have dubbed strokes brain attacks to make people realize that, just as with heart attacks, people with symptoms of stroke need to get to the hospital quickly. A very mild stroke (transient ischemic attack or TIA), in which stroke symptoms come and go within a few minutes or hours, is sometimes viewed as a warning sign for a subsequent large stroke.

Ted Baxter had no warning signs, no TIA. He was healthy as a horse, an avid exerciser, and took great care of himself. But he spent a lot of time on airplanes, including long airplane trips, and this requires some particular care due to the risk of deep vein thrombosis, or DVT. If you read the back of the airline magazines, they suggest exercises that will mobilize the blood in the veins of the legs and prevent the blood in the legs from stagnating and developing clots there. For most people, clots in the legs are risky because they can break loose, travel to the heart and then the lungs, and get stuck there as pulmonary emboli, or PE, which can be life-threatening. However, as Ted explains in his memoir, if the heart has a hole connecting the right side with the left side—a condition called patent foramen ovale, or PFO—then these clots can bypass the lungs and go directly to the brain. Ted indeed had a PFO, and that was the cause of his stroke.

The diagnosis and treatment of stroke has changed dramatically over the past several decades. Even as late as the early 1990s, the goal of a neurologist in treating an ischemic stroke (caused by lack of blood flow from a clot) was to prevent it from getting worse and to prevent any further strokes. The ability to intervene directly to undo the ischemia (i.e., to restore blood flow) was nonexistent. Several forward-thinking neurologists were experimenting with clot-busting therapies, but none were considered safe enough to apply broadly. That all changed in 1995 with the publication of two reports of clinical trials—one sponsored by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Study Group and the second by the European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study—showing the efficacy and safety of recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rt-PA) in breaking up clots and thereby reversing a stroke in progress. Since that time, if someone with an acute ischemic stroke comes to a hospital with a stroke center within a few hours (between three and four and a half hours, usually), they can receive advanced therapy to undo the stroke. For hemorrhagic strokes (those involving bleeding in the brain rather than clots), such stroke centers can also intervene rapidly.

Ted’s stroke was in 2005, at about the time that hospitals were beginning to become certified as stroke centers. Much of the national and regional infrastructure for advanced stroke care was not yet in place, although many of the top hospitals in the country were already developing such programs. Nevertheless, Ted did not receive rt-PA, and he developed significant damage to his brain. On this score, Ted is not unusual. Stroke patients who have received rt-PA have wide-ranging effects from the brain injury. It is hard to predict the benefits of rt-PA for an individual stroke patient, but receiving it earlier is better.

Although stroke risk and incidence increase with age, a stroke can occur at any time, even before birth. About 795,000 Americans will sustain a stroke this year, and many will be left with deficits in walking, talking, and other skills (e.g., using a dominant hand). Stroke is the leading cause of long-term disability in the United States and in many parts of the world. The most rapid phase of recovery occurs in the first six months, and subsequent gains are much slower and harder to achieve. Most people with strokes will not have as much recovery in the months and years after stroke as Ted Baxter, and as a result, we cannot underestimate the value of Ted’s messages of perseverance and determination.

One of the major manifestations of stroke is a difficulty communicating with speech. This disorder of speech and language following stroke, also accompanied by problems of memory, is called aphasia. It’s surprising how few people are familiar with this term, given that the disorder currently affects as many people in the United States as Parkinson’s disease—over a million Americans. From the Greek, meaning “without speech,” aphasia is far greater than lack of speech. It is a disruption of the entire brain system by which we communicate and understand meaning using abstract symbols, such as spoken and written words, signs (in the case of sign language), or the raised dots of cells (in the case of Braille). It also affects our ability to understand how those words are put together and how to disentangle the specifics of a message from its component parts. This system in the intact brain relies on complex interactions, still poorly understood, among many collections of neurons, or brain cells.

The left hemisphere of the brain plays a large role in understanding and producing speech sounds and single sentences, and the right hemisphere emphasizes the cadences of sentences and the understanding of longer passages. Damage to the left side typically causes far more severe problems with speech and language than the right. When a stroke affects the left side of the brain, as did Ted’s, neurons that contribute uniquely to these processes may die, and with them dies the ability to talk, to understand speech, to read, and—despite the book that lies before you—to write.

Similarly, the left hemisphere contains motor neurons that control movement on the right side of the body. So, too, Ted lost use of his right arm and leg. He learned to feed and groom himself with his nondominant left hand until he was able, through months of therapy and tireless exercise, to regain his strength.

Both of us have found ourselves, at various points, unable to walk and reliant on crutches to get around. Both of us required time to heal and physical therapy to strengthen before we were able to walk again, as did Ted. Yet both of us also knew with certainty that we would walk again, and that is a crucial difference. To work hard in full knowledge that your goal will be achieved is nothing more than common sense. To work unflaggingly toward a goal that may forever elude you is something else entirely, and it is this je ne sais quoi that makes Ted’s story so compelling. It is this quality that we ask of stroke survivors, that we wish we could prescribe, in order for them to achieve the inherently impossible-to-define goal of optimal recovery. In truth, however, neither of us believes that we, personally, would be able to fight adversity to this extent if faced with the same obstacles, even with our concrete professional knowledge that it would indisputably be the best course of action.

As is echoed throughout this book, Ted has a special trait, and a rare one. Even before we met him, he had beaten the motor deficit and was already walking, running, writing, and even golfing, using his right side as if it were always there for him. Of course it wasn’t, but through hard work, extreme dedication, and perseverance, he beat hemiparesis (weakness on one side of the body). We met Ted when he was still fighting the aphasia. Incredibly, although we know that he has aphasia, it is only because of our training that we know. Many of the people he meets in everyday life can’t tell. At one point, his golf instructor couldn’t tell. Did he have weakness? No. Could he walk? Yes. Did he have a mental disability? No. As far as he was concerned, he was fine.

Relentless

Relentless